A contemporary architect avoids trends by working with pure forms and natural materials.

Vincent Van Duysen began his career working for notable postmodernists, Ettore Sottsass and Aldo Cibic, who embraced ephemerality, complexity, and humor in their iconic designs. The founders of Memphis Milano, they invented the 80s style, with its intentionally disposable materials, slick surfaces and bright colors. One imagines our young Belgian architect in their Milanese office, trying to pick from an array of synthetic laminates when suddenly, he realizes that despite their clever patterns and whimsical prints, they’re all the same—all plastic. All fads that will quickly age with time.

An afternoon with VVD at his home in Antwerp, Belgium.

Finley Vintage in Honey VSB pairs perfectly with the color palette of VVD’s home.

When Vincent found his own practice in 1990, he chose a different path. His buildings, interiors, and furniture strive for timelessness. Though their forms vary, all his structures appear ready to withstand both the fickleness of taste and the ravages of time. Whether that makes them all uniquely of this moment, when meritocracy’s winners demand a luxury so subtle it’s almost invisible, or somehow beyond it, only the future will decide. But Vincent’s intentions remain clear, he believes that by surrounding ourselves with nothing but that which is necessary, thoughtful and true, we can achieve a state of grace—a meditative stillness akin to a religious experience. Or at least, after a long hectic day, find a bit of calm.

Vincent achieves this goal by combining modernist abstraction with pre-modern materiality so that a Vincent Van Duysen home can be simultaneously inspired by Le Corbusier and African mudbrick. Where modernists dispensed with ornament, Vincent goes further, by hiding air vents, gutters, hardware and transitions, anything that might distract from the play of light and shadow against pure form. However, his refinements don’t result in harshly minimalist spaces because he builds his worlds out of tactile materials like plaster, brick, wood, and stone that impart their own natural palettes and textures. The result is a serene environment, warm and contemplative, never stark or severe.

VVD wears Lachman while glancing through his books.

Vincent’s renown as an architect rests on a series of high-end residences that experiment with all-over cladding. He wrapped his DLC in smooth white stone; covered his HBH in fired clay tiles that mimic hand-split shingles; and completely clad his DC II in wood plank, with every gutter, ridge, and chimney concealed by sleight of hand.

Endless rows of wooden slats make up the exterior of his most original home, the TR Residence. Light reflects off the thin black boards and disappears into the crevices between them. This repetition of solid and shadow transforms into solid and sky when the slats lift off the wall to become the roof’s eaves. It’s an effect made even more magical by the primary occupants, horses, whose stables and grounds seamlessly integrate into the residence. It is perhaps the most exciting ranch since Luis Barragán’s San Cristóbal.

Vincent’s designed quite a few boxy all-brick Belgian homes, but the one that stands out dispenses with the flat top and instead features a monumental thatched roof, which hovers over white-washed walls separated by glass-curtained voids. Inside the VO, he selects startling surfaces like volcanic tiles around the oven range, leather ‘vegetal’ wallpaper in the home office, and a green mosaic spa. As an interior designer, Vincent prizes the surface of a wall over what is hung on it, the shape of space over what might fill it, the way light falls over the fixtures that dispense it.

VVD wears Lachman in Black.

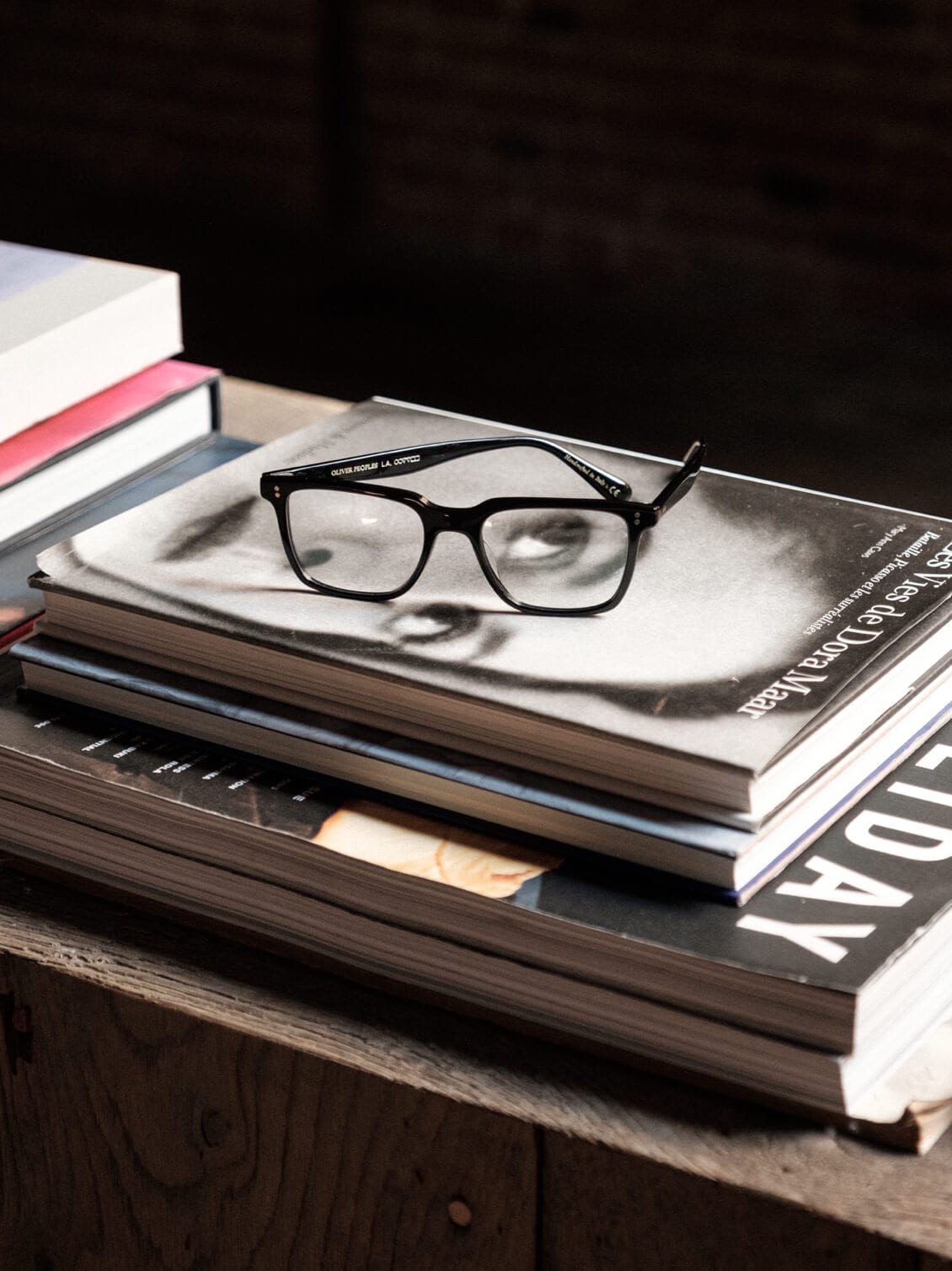

Lachman perched on some of VVD’s favorite books and magazines.

Vincent has yet to achieve his supreme goal: designing a church. But he recently transformed a 19th-century Augustinian convent into a boutique hotel, August in Antwerp. His respect for the monastic structure is evident. Unlike his more swashbuckling peers, Vincent’s light touch never overshadows the original listed building. Its neoclassical details are center stage, and his all-black interventions function like a backdrop that reveals them in their best light.

As his career progresses, Vincent will continue to blend Axel Vervoordt’s wabi-sabi interiors with John Pawson’s pristine forms. And hopefully soon, someone will let him design a contemporary chapel, as few architects are as gifted at representing the heavenly in the material.

Three years ago, Vincent was appointed Art Director of the storied Italian group, Molteni&C, which has produced furniture by Gio Ponti, Afra and Tobia Scarpa, Aldo Rossi and Jean Nouvel among others. This positions him as the heir to a lineage that has championed progressive design since 1934. However, where each of these designers saw themselves as pushing things forward with Ponti modernizing Italian upholstery, the Scarpas reinventing the leather chair, Rossi updating the Wiener Werkstätte, and Nouvel creating computer-aided furniture so stark it might poke your eyes out, Vincent sees his role as primarily holistic. He seeks to reunify all these traditions into a humane and sensible style that is a distillation of lessons learned.

Many modernist designers and architects that came before Vincent like Le Corbusier, Philip Johnson, I. M. Pei were known for wearing perfectly-round all-black spectacles—eyeglasses that became a trademark look. Seeing Vincent pose in a pair of Oliver Peoples, it becomes clear that these shades are the perfect metaphor for his project.

VVD with his dog, Gaston in his attic, what Vincent considers a personal sanctuary.

The new timelessness that Vincent chases isn’t pure abstraction, like Corb’s glasses, but rather a distillation of past heritage made modern and timeless, just like a pair of Oliver Peoples. It doesn’t demand that we fit it, instead, it fits us.

Vincent’s architecture perfectly fits the people who inhabit it. People of this time and place. People who want to avoid trends, exist outside of fashion, and live a thoughtful life. Vincent succeeds in creating a timelessness that is perfectly suited to today.

Words: Jared Frank

Photos: Thibault De Schepper