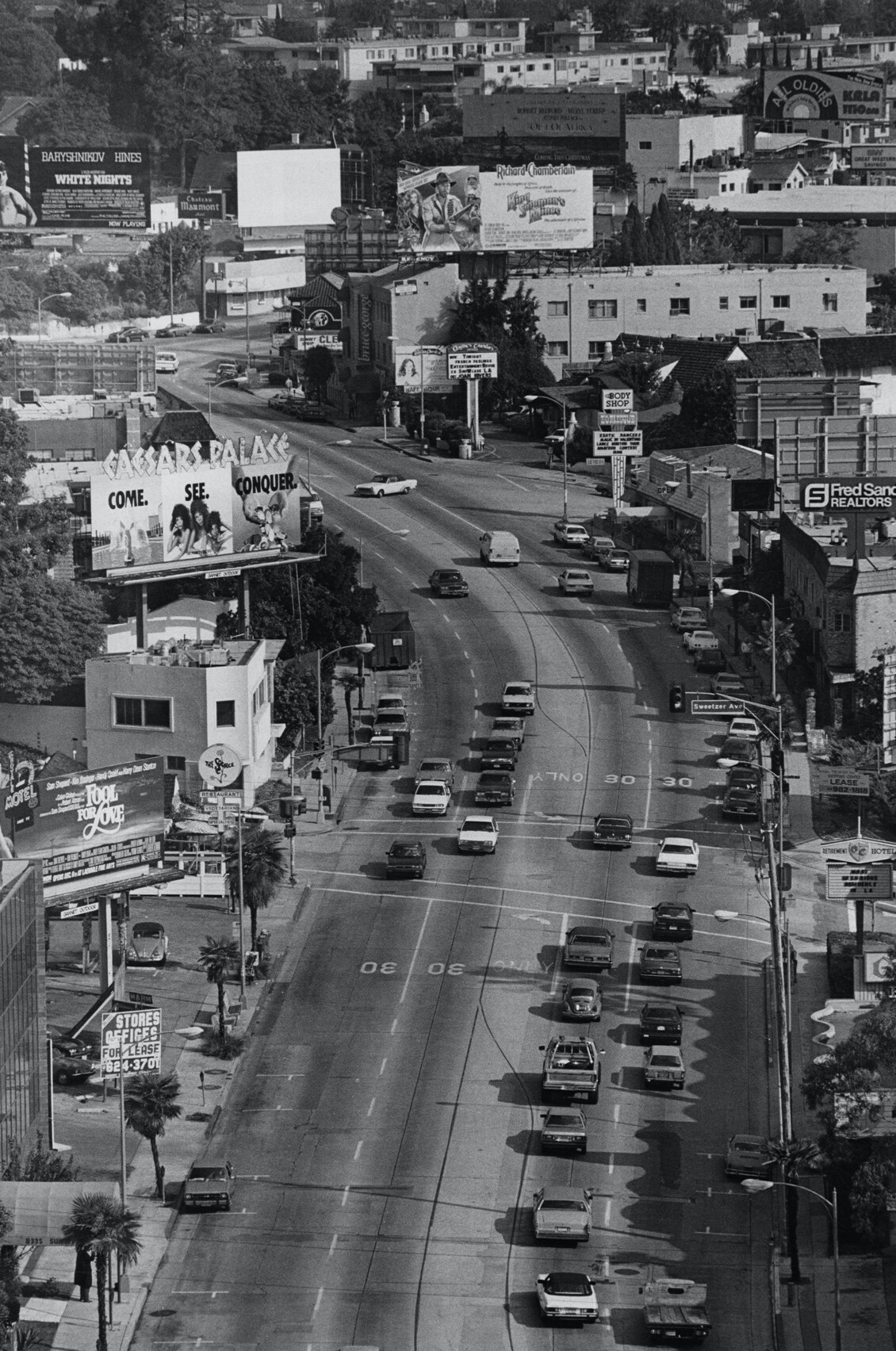

Sunset Boulevard, a microcosm of nostalgia that inspired Oliver Peoples.

It has to start with the light. Any story about Los Angeles has to mention the golden light ... and then maybe palm trees and Hollywood mythology, vernacular architecture, beautiful cars and beautiful people.

Chateau Marmont at the Morton’s Rest in Los Angeles. Photo by Ron Galella via Getty Images.

If you want all of that in one aesthetically focused moment, you could do no worse than to stand anywhere along Sunset Plaza, the time-forgotten, much-beloved stretch of shops and restaurants in the middle of the Sunset Strip. As if frozen in Jurassic amber, these few blocks have barely changed in all their years of existence. In a city known for carelessly destroying its past, Sunset Plaza has miraculously remained much the same since about, well ... 1924!

Hollywood history was made on this strip of the Strip—it’s where George Hurrell had his photo studio, the great interior designer Billy Haines had his showroom, and fashion designer Don Loper also had his. Famed MGM costume designer Adrian (The Women, The Wizard of Oz) opened an antiques shop there. Café Trocadero, the legendary nightclub, was happening from 1934 to 1947. These few blocks have been a stylish refuge and a see-and-be-seen nucleus for decades. It was mainly for insiders and remains that way to this day, beautiful losers and brilliant dreamers alike.

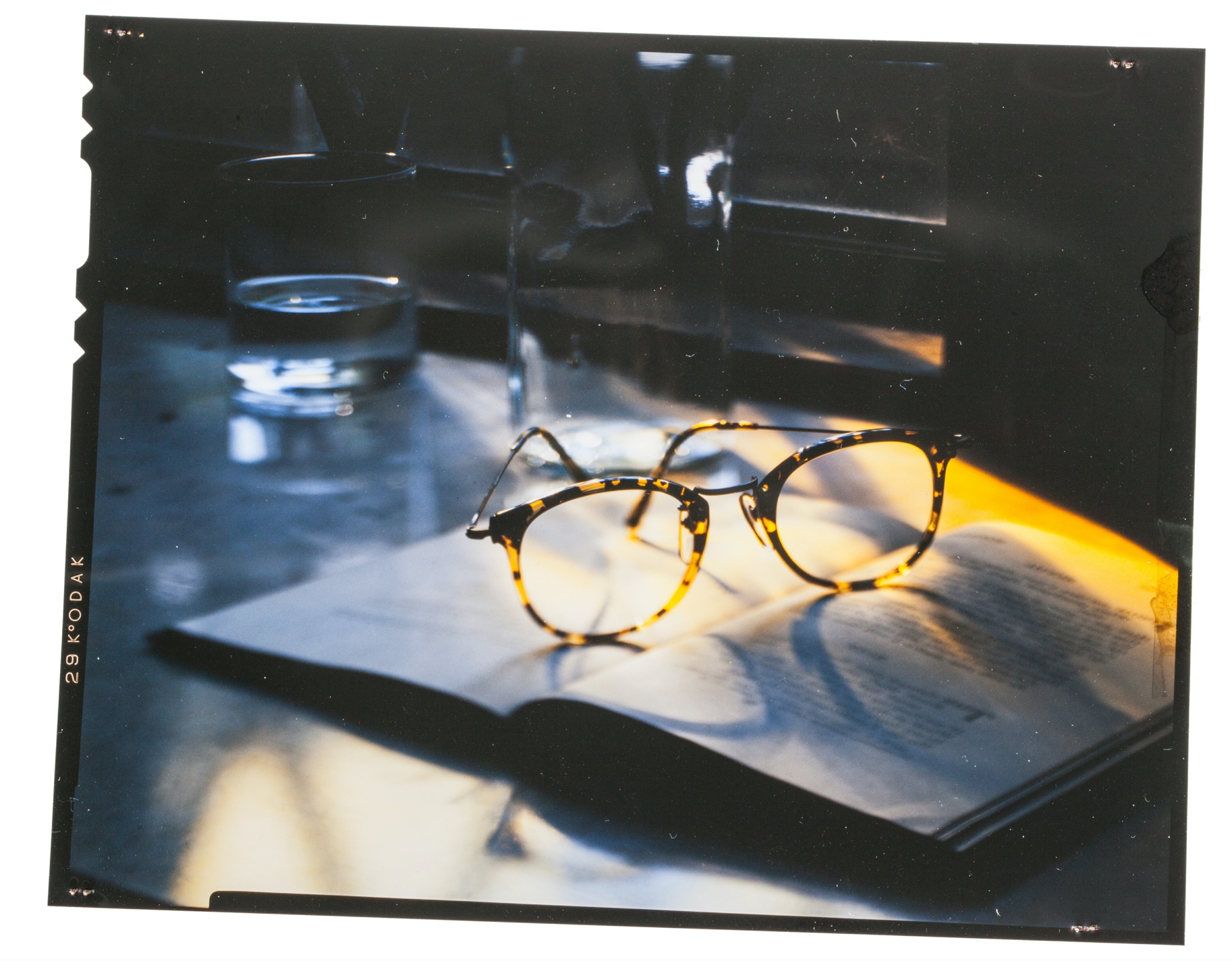

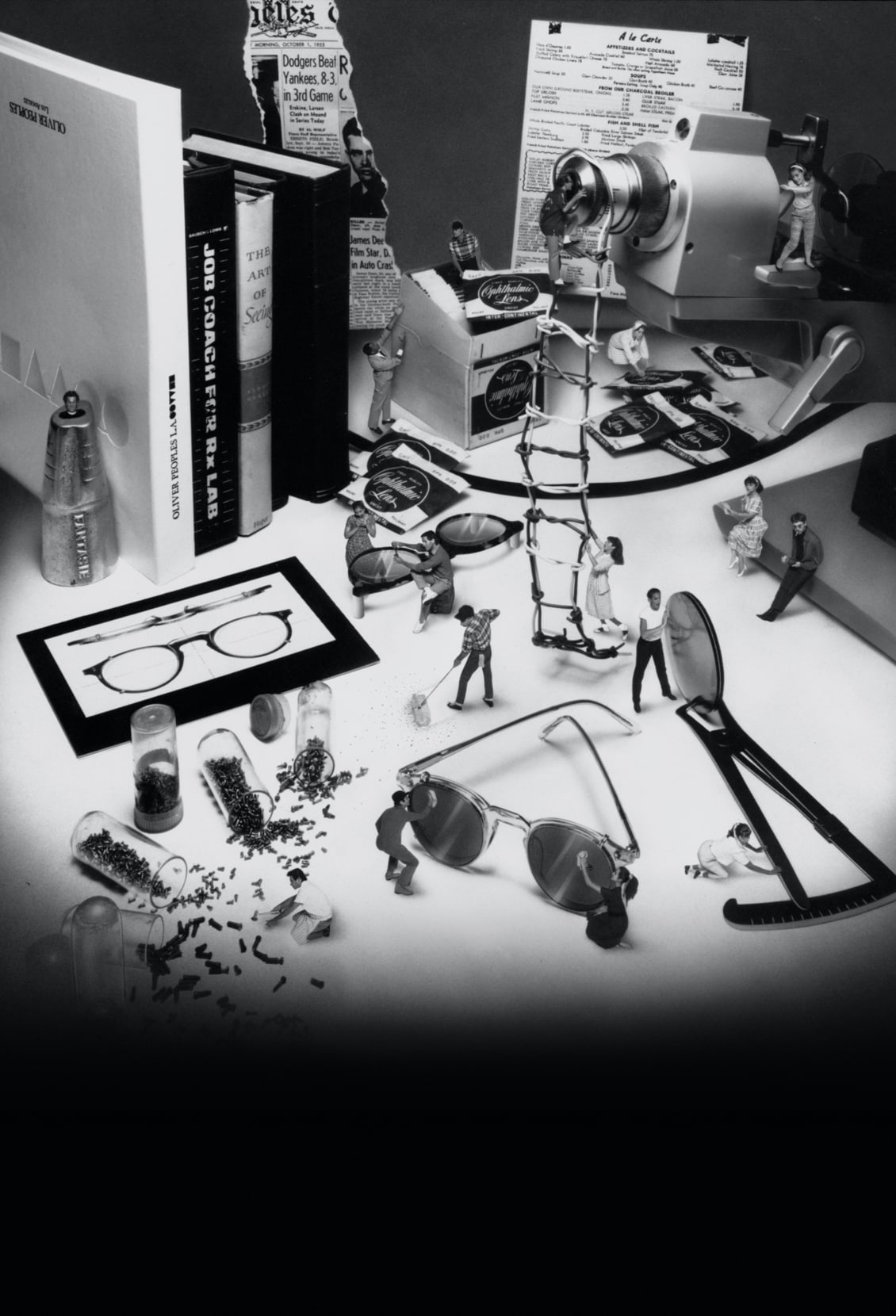

Original film of the Oliver Peoples OP-506.

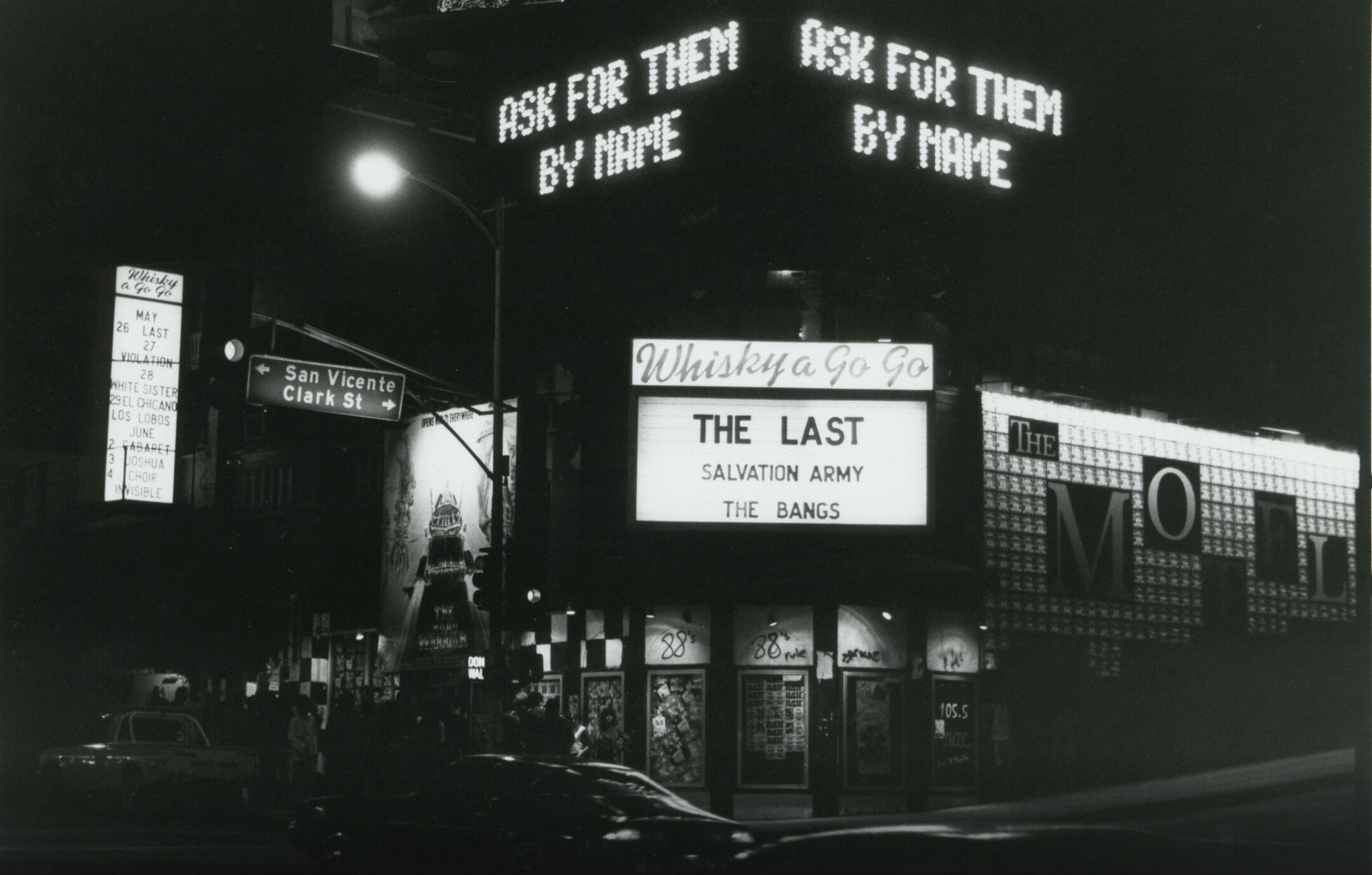

Sunset Plaza is bookended, in either direction, by a hedonistic history of rock and roll/ youthquake upheaval. The famous teenage riots of 1966 were epicentered around Crescent Heights and Pandora’s Box to the east. Punk in the late ’70s, then hair-metal bands and their crües all through the ’80s, partied hard and into legend to the west, buzzing around the main clubs—The Whisky a Go Go, The Roxy, and Gazzarri’s. After those clubs closed for the night, hanging out until dawn in the Rainbow parking lot, waiting for something to happen, or someone to corrupt you, was a ritual. Welcome to the jungle, baby.

Yet, as if in the calm of the hurricane, especially in the ’80s—a real vortex moment for Sunset Plaza—one could find Nancy Reagan and Betsy Bloomingdale or their conservative ilk at their poodle parlor Jessica’s Nail Clinic while David Geffen, Berry Gordy and Mike Ovitz would mingle with Don Johnson, Roger Moore or Sly Stallone over power lunches at Le Dome, the restaurant du jour, cofounded by Sir Elton John (who would become one of Oliver Peoples’ biggest fans). It was Hollywood lifestyles of the rich and famous all within the safe confines, under the canvas awnings and alongside the valet parkers, of Sunset Plaza.

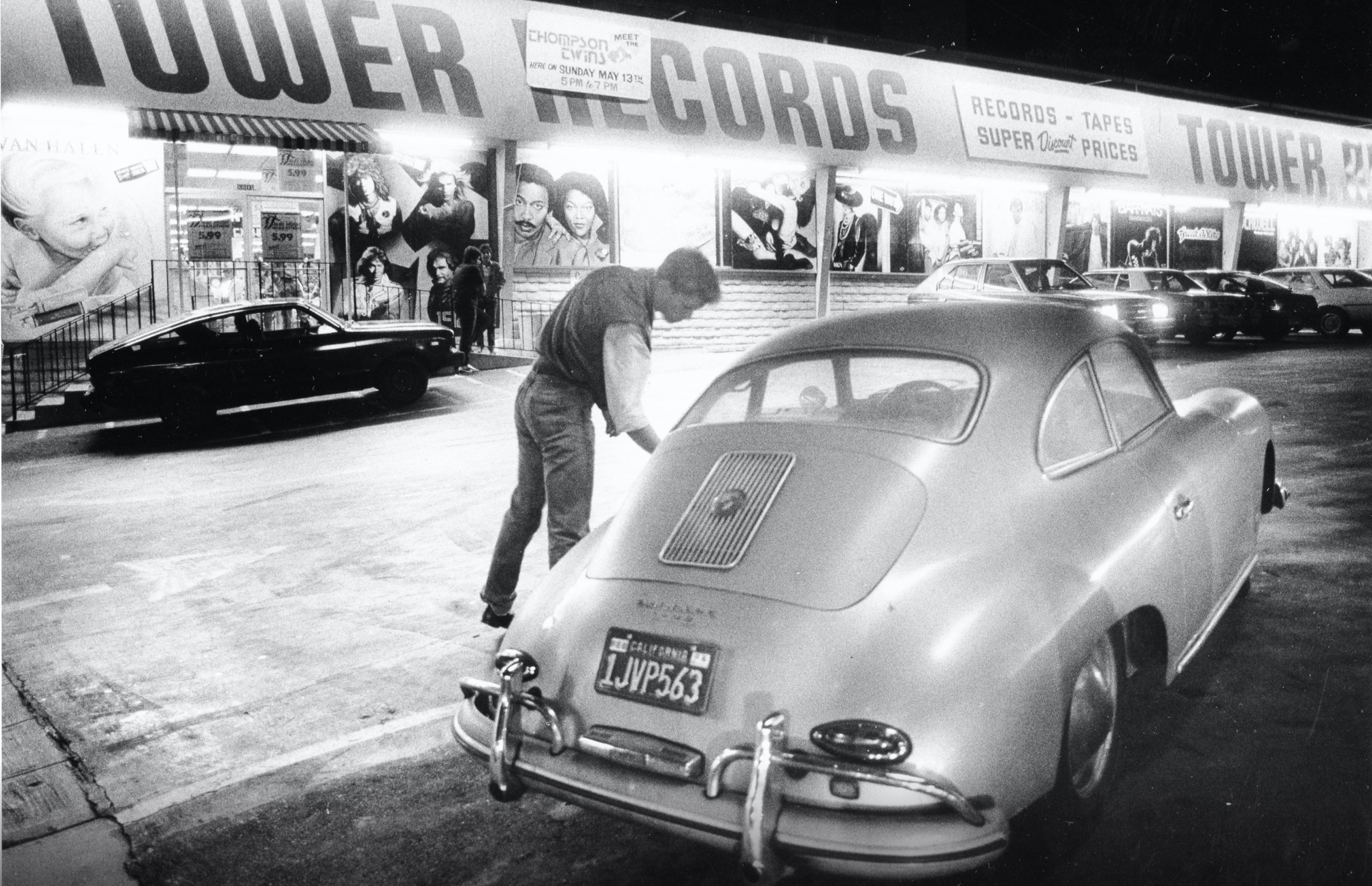

Beautiful classic cars lined up in front of Tower Records on Sunset Boulevard. Photo by Janet Knott/The Boston Globe via Getty Images.

Across the street, pioneering retailer Charles Gallay opened his eponymously named shop, the first boutique in America to carry Azzedine Alaïa, in an equally impressive minimalist interior. There was also a legendary tradition at Gallay that the young and unworldly beautiful starlets who shopped there would autograph one of the walls, their penmanship now no doubt buried under layers of stain blocker.

The ’80s, especially a particularly money-scented, Hollywood-centric circle, were immortalized in Paul Schrader’s zeitgeisty film American Gigolo —Armani suits, “rolling in designer sheets,” black Mercedes SL convertibles, et al. The location used for the apartment of the Richard Gere character, Julian, was just steps behind Sunset Plaza, and the Paul Williams–designed, black-and-white striped, very Hollywood Regency-style complex complimented the Plaza perfectly as if it were the dormitory (sadly bulldozed a few years ago). The soundtrack was a decidedly sexy and modern Giorgio Moroder–driven mechanical beatfest and precisely, exuberantly, evocative of the era. Call me ... on the line. Sunglasses, designer sunglasses, were needed more than ever after an ’80s all-nighter. Even paradise has a serpent in the grass.

Oliver Peoples’ first business card.

Oliver Peoples’ first advertising campaign, “Working Opticians,” featuring its own employees as opticians. Photo by Wynn Miller.

It’s 1987 and at 8642 Sunset Blvd., right in the middle of Sunset Plaza, Oliver Peoples is opening its first retail space. It didn’t open, really, it happened. It was the perfect combination of product and location, the right time and place for the shop to be born. At first visit it was so evident—their love for beautiful eyewear— mainly culled from the most glamorous years for shades, the 1920s to the 1960s. But they also genuinely cared about the crafting of their lenses and gave you such personal attention and style consultation that you felt like a celebrity. It was an eyewear salon. They loved what they did and they, in turn, would end up being loved by the Hollywood people, the Society people, the rock and rollers—all would become Oliver Peoples' people. Looking back there was hardly a precedent for Oliver Peoples. Before them, everyone reluctantly bought boring prescription eyeglasses, whatever one could find from an optometrist or optician’s shop. Yes, L.A. Eyeworks had opened in 1979 down on Melrose, but their designs were more new wave, more extreme and contemporary, geared for a louder crowd, bold and original, but not classic and steeped in history like Oliver Peoples’. About the only American sunglasses worthwhile at the time were Ray Bans—“Wayfarers” or “Aviators”—which were and still are great, but there was no range or great quality easily available otherwise, certainly not new-in-box vintage or well-made, retro-styled frames.

The Whiskey a Go Go, captured here in the 1980s, retains its iconic status today. Photo by Gary Leonard/Corbis via Getty Images.

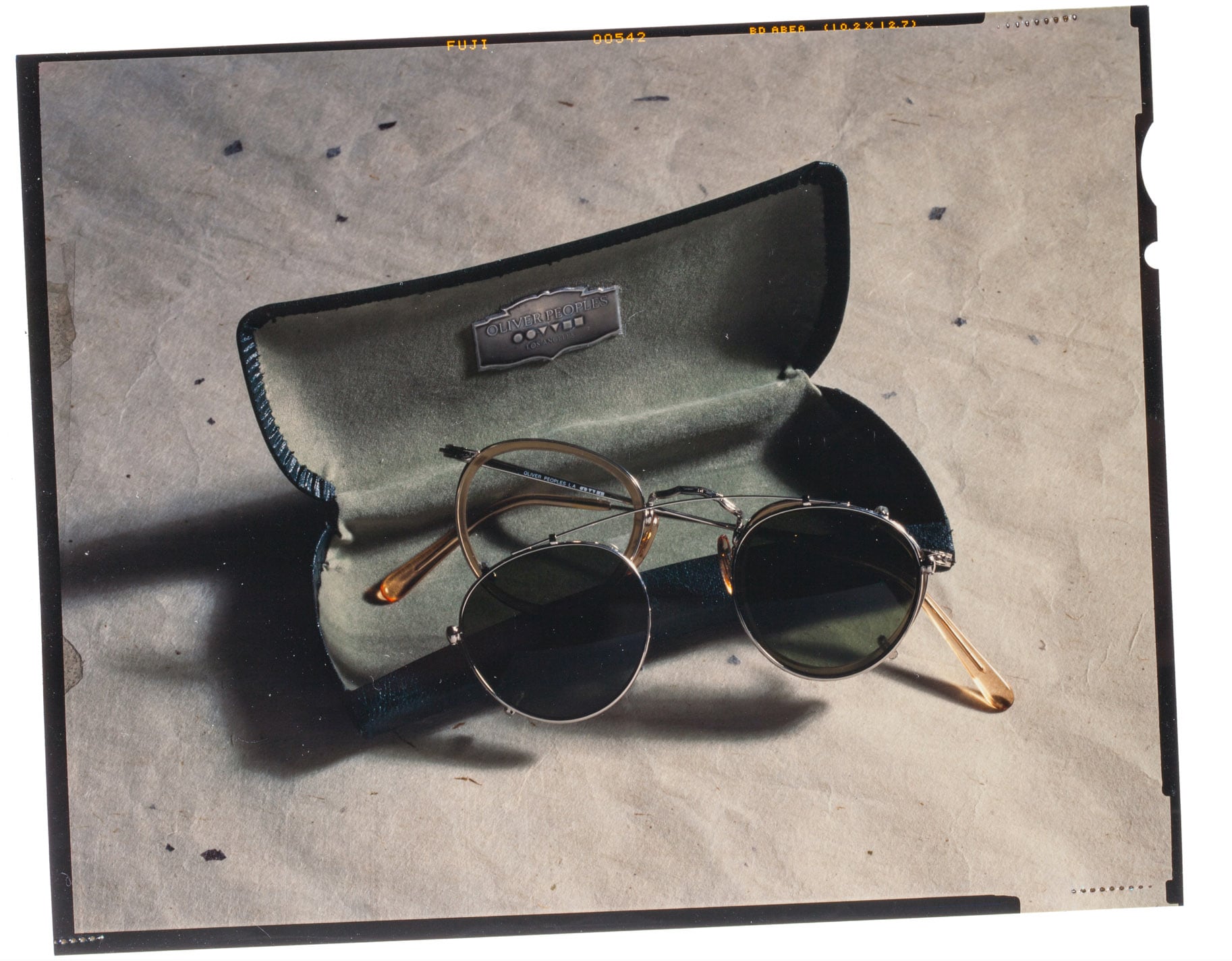

I think the first glasses I bought from Oliver Peoples were the horn rimmed with clip-ons. No one had ever managed to make clip-ons cool before, they were only associated with old geezers. Yet it was exactly the right time to reintroduce them, completely fresh and original, daring even. It was one of the earliest moments of the “nerdy cool” revival. We became a little clique, a little club—those who wore Oliver Peoples.

It was even radical at the time to be unisex; I don’t recall if Oliver Peoples even had a separate men’s and women’s section as was tradition—it was just all about style. It was very Old Hollywood/New Hollywood. Sporting their frames was a proud status symbol and signifier. That still rings true to this day. By embracing and so loving past styles, Oliver Peoples has redefined Hollywood style itself, becoming one of the main purveyors of it, postmodernly morphing old and new into something completely unique and perfectly reinvented.

Billboard ads along Sunset Strip. Photo by Paul Chinn via the Herald Examiner Collection/Los Angeles Public Library.

The Sunset Tower Hotel on the Sunset Strip in 1991. It was designed by Leland A. Bryant in the Art Deco Style in 1929. Photo by Santi Visalli via Getty Images.

The names on the windows may change but the architecture and ambience of Sunset Plaza is wonderfully stubborn, heels dug in against the hurricane force of current Los Angeles development (tall hotels and condos are beginning to sprout, intimidate, on either side of the Plaza along Sunset Boulevard, both to the east and west).

Yet, as it has for decades, each morning the sun rises on Sunset Plaza anew, these few blocks continually evolving while staying the same. Remnants of the previous night’s revelry are hosed off the wide sidewalks; awnings are cranked out to shade the café, and valet parkers are manning their posts. A new cast of characters begins to trickle into the shops and cafes, a screenplay is being doctored over a late breakfast at Mel’s, and a new girl arrives from Illinois. Hollywood life starts all over again and Oliver Peoples is open for business.

An archive photograph of the MP-2 clip.

WORDS: Lisa Eisner and Brad Dunning